- 1. Educación Antigua y Educación actual con las herramientas digitales. Por: Joselyn Carreño Fecha: 16/04/2014 Curso: “1ro C”

- 2. Educación Antigua ¿Cómo fue la educación antigua? En las ciudades y aldeas había maestros que enseñaban las primeras letras en escuelas mixtas, de niños y niñas. Entre el pueblo había iletrados pero también había quienes sabían leer y escribir. Sin embargo, sólo los varones de familias acomodadas seguían estudiando después de los doce años. Un "gramático" o profesor de literatura iba a su casa para que estudiaran los autores clásicos y la mitología. Los jóvenes ricos estudiaban para cultivar su espíritu, no para "ganarse el pan" o para integrarse a la vida pública. Las materias que aprendían estos jóvenes tenían un valor "de prestigio" porque embellecían su alma, como la retórica, que era el arte de hablar elocuentemente en público. Todos los muchachos aprendían modelos de discursos judiciales o políticos.

- 3. Desventajas de la educación antigua El maestro o instructor no siempre está preparado para controlar un grupo o transmitirle su enseñanza Al alumno en muchos casos le impone la presencia del maestro al frente del grupo. En ocasiones en grupos muy numerosos una técnica didáctica mal aplicada puede generar aburrimiento o distracciones en el aprendiz. No se dispone de fuentes a la mano para poder aclarar una duda o concepto erróneo surgido en el momento. En ocasiones al ser evaluado el alumno tiende a copiar. Autoritarismo del maestro del siglo pasado.

- 4. ¿Qué diferencia hay entre educación actual y la de antes? ♥ La educación actual enfoca al hombre como organismo inteligente que actúa en un medio social. ♥ En cambio la educación antigua concibe al hombre como un receptor del conjunto de contenidos que la sociedad considera valiosos, conjunto que es reducido a ideas o conocimientos.

- 5. Herramientas digitales Las herramientas y conocimientos para desarrollar las competencias digitales Ejemplos celular blogs Gmail

- 6. Hoy en día, el acceso fácil al conocimiento mundial, que se ha dado, en gran medida, al desarrollo Tecnológico, y con ello me refiero a Internet, no da cabida a excusas, y es imperativo aprovechar el tiempo efectivamente para adquirir y generar más ideas de desarrollo. Por ello es importante acoplarse a las nuevas tendencias que exige la modernidad tecnológica y la educación, preparándose constantemente para responder a la competitividad de un día a día cambiante, mediante el estudio continuo y adhesión de nuevos conocimientos.

- 7. ¿Qué son? Su uso Son todos aquellos software o programas intangibles que se encuentran en las computadoras o dispositivos, donde le damos uso y realizamos todo tipo de actividades y una de las grandes ventajas que tiene el manejo de estas herramientas, es que pueden ayudar a interactuar más con la tecnología de hoy en día. Permiten que dos o más personas establezcan comunicación por medio de mensajes escritos o video desde distintas partes del mundo en tiempo real. Además de la posibilidad de que la información circule de manera rápida y efectiva. En educación para que el trabajo en clase sea más entretenido y provechoso. Son un material de apoyo para enriquecer el contenido que se aborda, los alumnos pueden buscar más datos un tema de su interés.

Paranapanema, SP - Brasil - / Being useful and productive is the aim of every knowledge acquired / - Quod scripsi, scripsi. - Welcome !

quarta-feira, 16 de abril de 2014

Educación antigua y educación actual con las herramientas digitales

Como saber se um cartucho de impressora está queimado

Se algum cartucho da sua impressora insiste em não funcionar, pode ser que ele esteja queimado. Em alguns casos, pode ser que seja apenas uma falha no reconhecimento do cartucho. Mas se o problema permanecer é preciso ter certeza se ele está queimado, o que pode evitar desperdício e uma compra desnecessária. Para isso, veja algumas dicas que o TechTudo preparou.

Qual impressora tem o cartucho mais barato do mercado?

Descubra se o cartucho está realmente queimado (Foto: Montagem/Edivaldo Brito)

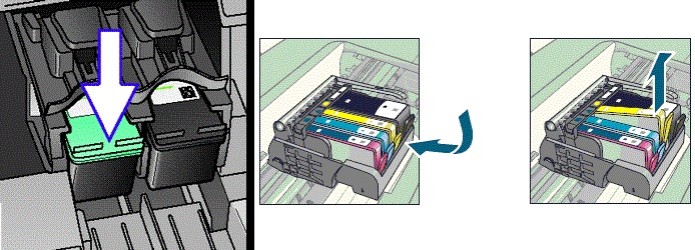

Antes de fazer qualquer coisa, certifique-se de que os cartuchos foram instalados corretamente e que eles são compatíveis com o equipamento. Para fazer isso, consulte no manual da impressora ou no site da fabricante, e confira a identificação dele. Se for confirmado que o cartucho que está sendo utilizado é o correto, será necessário fazer alguns procedimentos para verificar se ele está queimado.

Como não é possível identificar se um cartucho está ou não queimado apenas olhando para ele, a primeira coisa a ser feita é colocá-lo na impressora e observar como ela reage, e se reconhece o cartucho. Caso não reconheça, para verificar se todos os cartuchos estão limpos e encaixados corretamente, faça os procedimentos de inspeção e limpeza. Depois, teste novamente. Se mesmo depois desses procedimentos a impressora continuar não reconhecendo o cartucho, é quase certo que ele está queimado.

Retire o cartucho da impressora (Foto: Divulgação/HP)

Em último caso, experimente também desinstalar e instalar novamente o software da impressora usando o disco de instalação que acompanha o produto ou baixando no site do fabricante.

Antes de decretar o fim do cartucho, experimente colocá-lo em uma outra impressora que seja compatível com ele (lembre-se de consultar o manual da impressora para ter certeza). Caso ele seja reconhecido e funcione, então o problema não está nele e sim na impressora.

Até o momento, todos os testes realizados são baseados na eliminação das possíveis causas do não funcionamento do cartucho. Porém, existe uma forma mais direta de avaliar se ele está mesmo queimado: usando um testador de cartuchos. Um testador de cartuchos é um aparelho de baixo custo e muito simples de usar. Existem diversos modelos no mercado e normalmente existe um para cada série de cartucho.

Testador de cartucho (Foto: Divulgação/Nolleta)

Para usar essa abordagem é necessário comprar um aparelho ou usar o de alguém que já tenha. Para segunda alternativa, você pode recorrer a alguma empresa que faça reciclagem de cartuchos. Mas lembre-se, use apenas um testador compatível com o cartucho a ser avaliado.

Para usar o aparelho você só precisa encaixar o cartucho no local indicado e observar se todas as luzes acendem. Se isso acontecer, o cartucho está com o circuito eletrônico em perfeito estado. Se apenas algumas luzes acenderem, o cartucho estará parcialmente queimado. Dependendo do modelo do testador, a partir de uma determinada quantidade de luzes que não acendem (verifique no manual), é recomendável não utilizar o cartucho.

Depois de confirmar que o cartucho está realmente queimado, só resta substituí-lo por um novo.

Como desentupir o cartucho da impressora? Confira no Fórum do TechTudo.

Giant Gamma Ray Detector Searches for Two Home Sites

The Cherenkov Telescope Array will track high-energy photons to probe black holes, dark matter and relativity

The telescope array (artist’s impression) will be split across the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

Credit: DESY/Milde Science Comm./Exozet

When very-high-energy gamma-rays slam into Earth’s atmosphere, they trigger particle showers that emit a faint blue light. With this light, astronomers want to trace the rare gamma-rays — only a few strike each square meter of the atmosphere each month — back to their sources, violent objects such as supermassive black holes. But first researchers must find a home for the planned €200-million (US$277-million) Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA) — or rather, two homes. The telescope will be made up of a 19-dish array in the Northern Hemisphere and a 99-dish array in the south.

At a meeting in Munich, Germany, on 10 April, representatives from the 12 CTA partner countries inched closer to picking the sites. In the Southern Hemisphere, they narrowed the list down to two possibilities: Aar, in southern Namibia; and Cerro Armazones in Chile’s Atacama Desert. In the north, four sites remain in the running: two in the United States and one each in Mexico and Spain.

Some had hoped the panel would pick firm favorites. Last year, a committee of CTA scientists came up with a broader list of sites based on environmental factors such as weather and earthquake risk. The latest decision adds considerations such as political stability and the financial contributions of host nations. “The process is going slower than we’d like, but it’s going, and that’s great,” says Rene Ong, a physicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has helped to plan for the CTA.

The array would study photons in an as-yet unexplored energy region: up to 100 teraelectronvolts. Cosmic rays — protons and other nuclei — emit these photons when they are accelerated at the surface of neutron stars and black holes, and when they collide in stellar winds.

The CTA would focus on the center of the Milky Way because of the dark matter thought to lurk there; many theories predict that dark-matter particles could annihilate each other and emit gamma-rays that the CTA should detect. The array would explore physics at energy scales well beyond the scope of most powerful accelerators.

The CTA would also probe theories of quantum gravity, which try to reconcile quantum mechanics with Einstein’s theory of gravity. Some theories predict that very-high-energy photons, with wavelengths approaching the foamy quantum scale of space-time, will travel slightly slower than lower-energy photons from the same source. Observations of gamma-rays at different energies could reveal arrival-time lags.

The CTA panel aims to pick a final southern site by the end of the year. Choosing the northern site may take longer, says panel chair Beatrix Vierkorn-Rudolph, deputy director-general of Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Astronomers hope to be ready to start construction by the end of 2015 and to begin full operations in around 2020.

This article is reproduced with permission from the magazine Nature. The

article was first published on April 15, 2014.

Microrobots, Working Together, Build with Metal, Glass, and Electronics

Tiny robots that work together like ants could lead to a new way to manufacture complex structures and electronics.

- By Tom Simonite on April 16, 2014

Why It Matters

Existing mass production technology is inflexible and still relies on humans for many tasks.

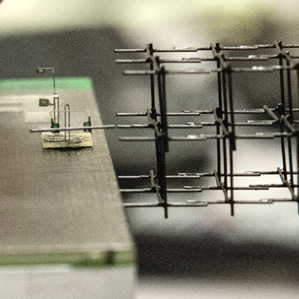

Building big: A team of three small, magnetically steered robots worked together to build this structure from toothpick-sized carbon rods. Someone glancing through the door of Annjoe Wong-Foy’s lab at SRI International might think his equipment is infested by ants. Dark shapes about a centimeter across move to and fro over elevated walkways: they weave around obstacles and carry small sticks.

A closer look makes it clear that these busy critters are in fact man-made. Wong-Foy, a senior research engineer at SRI, has built an army of magnetically steered workers to test the idea that “microrobots” could be a better way to assemble electronics components, or to build other small structures.

Wong-Foy’s robotic workers have already proved capable of building towers 30 centimeters (two feet) long from carbon rods, and other platforms able to support a kilogram of weight. The robots can work with glass, metal, wood, and electronic components. In one demonstration, they made a carbon truss structure with wires and colored LEDs mixed in to serve as the lab’s Christmas tree.

“We can scale to many more robots at low cost,” says Wong-Foy, who thinks his system could develop into a new approach to manufacturing. Many electronic components are the right size to be handled by his microrobots, he says, and teams of them might prove a good way to lay them out onto circuit boards.

SRI wants to create a version of the microrobot system that could be sold to other research labs and companies to experiment with. “We’ve demonstrated the basic platform and are now looking at how we can transfer out of the lab as a research platform,” says Rich Mahoney, director of robotics at SRI. “You should be able to buy this on the shelf.”

SRI’s microworkers are simple: just small magnetic platforms with simple wire arms on top. They can move only when placed on a surface with a specific pattern of electrical circuits inside. Sending current through the coils beneath exerts a force on the magnets and steers the robots around. Wong-Foy has written software to do that, and used it to choreograph the movement of over 1,000 tiny robots in a complex circulating pattern. That shows it should be possible to have them work in large teams, he says.

The robots’ wire arms are unable to move independently. But creating teams of robots with different types of arms makes it possible to do complex work.

Building a truss structure requires three types of workers. One operates a kind of toothpick dispenser, pushing a lever to release a toothpick-sized carbon rod. Another robot dips its arms into a water trough to put droplets on the ends of its arms, and then uses surface tension to pick up the rod. A third robot visits a glue station, dipping its arms and then applying the glue to the structure under construction. Finally, the robot that picked up the rod presses it into place and waits for an ultraviolet light to switch on to cure the glue. Then it can withdraw to pick up a new rod.

The software controlling the robots can also move the platform they are sitting on. It moves the platform each time a new layer is complete so the robots’ working space stays the same as the structure they’re building grows.

Much like 3-D printing technology, microrobots promise to be a more efficient way to make complex objects in small quantities than conventional mass-production technology, says Mahoney. That’s partly because the microrobots can be reprogrammed to do completely new tasks, and partly because they’re inexpensive. “We sometimes call this megahertz manipulation,” he says. “We can think of manipulation at rates we’re used to seeing in information processing.”

Helping to make circuit boards in small batches for prototyping new electronic devices is one possible application. Hobbyists and small companies working on electronics hardware today make few prototype circuit boards due to the time it takes to assemble them by hand, and the expense and delay of paying for small runs at dedicated plants.

Wong-Foy also thinks his approach might be useful for assembling devices that combine electronic and optical components, for example to interface with fiber optic cables. Because silicon and optical components can’t be processed in the same step, that industry often uses manual assembly to put them together. “In the field of optical electronics people have not found a good way to integrate indium phosphide lasers with silicon components,” says Wong-Foy. “The scale of those things is the size of carbon rods we’re using here.”

Apple, Google, Microsoft e outras empresas se unem para diminuir roubo de smartphones

As cinco maiores operadoras dos Estados Unidos e as principais fabricantes de smartphones assinaram um acordo para tentar diminuir o roubo de aparelhos. As empresas concordaram em implantar tecnologias que permitam apagar o conteúdo remotamente e inutilizar o dispositivo, impedindo que um ladrão ou um receptador ative o smartphone sem a permissão da vítima.

Podem até roubar, mas vai ser muito difícil usar o aparelho

Entre as fabricantes que assinaram o acordo estão Apple, Google, HTC, Huawei, Motorola, Microsoft, Nokia e Samsung — ou seja, as desenvolvedoras dos três sistemas operacionais móveis mais usados do mundo e algumas fabricantes-chave. A medida vale para todos os aparelhos vendidos a partir de julho de 2015, e as operadoras americanas concordaram em facilitar o funcionamento dessas tecnologias.

Não é como se tudo fosse mudar da noite de 30 de junho para a manhã de 1º de julho de 2015: algumas empresas já começaram a agir antes mesmo do acordo ser assinado. Android, iOS e Windows Phone já possuem nativamente um recurso que permite localizar o dispositivo perdido em um mapa, soar um alarme ou apagar o conteúdo do aparelho, para evitar que as informações caiam em mãos erradas.

O iOS está um pouco à frente por possuir o Bloqueio de Ativação, que inutiliza um iPhone roubado. Hoje, para restaurar o aparelho para as configurações de fábrica ou mesmo ativá-lo, é necessário ter a senha do iCloud do proprietário — se você levar um iPhone para uma assistência técnica, certamente receberá a instrução de desativar a função Buscar iPhone antes de entregar o aparelho.

Embora o acordo tenha sido assinado nos Estados Unidos, a medida deve afetar aparelhos vendidos em todo o mundo. É provável que Android e Windows Phone, por exemplo, tenham algo parecido com o Bloqueio de Ativação em uma versão futura. Só o fato das operadoras terem concordado é um grande avanço: o The New York Times publicou em novembro a informação de que as operadoras não viam o acordo com bons olhos porque passariam a vender menos seguros de smartphones.

Telefonia móvel: onde foi que erramos?

-

- Por Dane Avanzi

No fim de 2013, a operadora francesa Iliad anunciou a inclusão do serviço de 4G, sem custos adicionais, ao seu pacote de serviços “free mobile”, que custa 19,99 euros mensais e pode ser contratada sem um período de carência longo – exigência comum em contratos com operadoras móveis nos casos em que há redução de custo significativo da tarifa. O que é inédito nesse caso é o fato da operadora “espontaneamente” oferecer um “upgrade” de plano a seus clientes. Mas por que a operadora fez isso? Certamente para ganhar mercado das grandes empresas, no caso, a Orange, a SFR, da Vivendi, e a Bouygues Telecom. Nova no mercado, a Iliad – que desde 2012 já cresceu 11% segundo dados da agência reguladora francesa – tem como principal estratégia oferecer o mesmo serviço das concorrentes a preços baixos.

Enquanto na França o serviço está cada vez melhor e mais barato, no Brasil andamos a passos largos na direção contrária. Onde foi que erramos? Penso que a resposta dessa pergunta é bastante complexa, como a maioria dos problemas brasileiros. No entanto, voltando às origens do processo de privatização da Anatel (Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações), podemos encontrar o fio da meada e avaliarmos o que pode ser melhorado.

Antes de 1997, a telefonia móvel no Brasil era administrada em todo o território nacional pela Telebrás, controladora de inúmeras empresas estatais regionais tais como, Telesp Celular, Telemig, Telenordeste Celular, entre outras. Com a privatização ocorrida em 1998, todas as empresas passaram a ser geridas por empresas privadas. Com o intuito de incentivar a competição, a Lei Geral de Telecomunicações, de 2003, previu a criação de empresas espelhos para concorrer com as teles recém-licitadas, que haviam herdado todo o legado das estatais recém-vendidas.

Empresas como Vésper, Intelig, Tess (atual Claro), são remanescentes dessa época e foram sendo ao longo dos anos compradas pelas grandes com o aval complacentes das autoridades brasileiras. Penso que o cerne da questão da falta de concorrência entre as operadoras brasileiras seja a falta de novos players no mercado. Tal movimento de fusão de empresas do setor somente se intensificou ao longo dos anos, sendo o último episódio da possível união entre Vivo e Tim, por ora abortado pela Telefônica e Itália Telecom, suas respectivas controladoras.

Outro fator que torna o Brasil o “paraíso” das teles é a falta de prestação jurisdicional. A morosidade da Justiça brasileira, que permite uma infinidade de recursos, acostumou as operadoras a descumprirem reiteradamente metas de qualidade, além de constarem no topo da lista do Procon de cobranças indevidas. Afora isso, temos uma das maiores cargas tributárias do mundo que oneram muito o setor de telecomunicações.

Como se vê, restabelecer o ambiente de competição que permita que novas empresas ingressem no mercado pode ser o primeiro passo para baixar o valor da conta dos brasileiros. Quem sabe a Anatel, inspirada em casos positivos como esse da França, promova o leilão dos 700 mhz com novas regras que resultem em economia para os brasileiros. Os consumidores agradecem!

-

- Dane Avanzi Diretor Superintendente do Instituto Avanzi, ONG de defesa dos direitos do Consumidor de Telecomunicações

Publicada em 16/04/2014 8:48

São Paulo ganha primeiro caixa eletrônico de Bitcoin - e fica em um bar!

A ATM foi apresentada pela primeira vez na Campus Party, em janeiro. Ela é também a primeira da América Latina.

A cidade de São Paulo ganhou o primeiro caixa eletrônico de Bitcoin da América Latina. A máquina foi instalada no início da semana pela empresa Mercado Bitcoin no Bar do Zé Gordo, no bairro Itaim Bibi, na capital paulista - e claro, o local também aceita pagamentos de contas com a moeda virtual.

A Mercado Bitcoin afirma que a escolha do local se deu pela proximidade com escritórios de tecnologia e bancos e a ideia de trazer a novidade à cidade é, principalmente, testar a aceitação das máquinas. Vale lembrar que a máquina só aceita cédulas de reais e faz a conversão do dinheiro em cédula para Bitcoin.

O equipamento foi fabricado pela empresa portuguesa Lamassu e foi apresentado pela primeira vez durante a Campus Party, em janeiro.

Ganhando força

Estima-se que cerca de 50 estabelecimentos brasileiros aceitem Bitcoins atualmente. Além do Bar do Zé Gordo, que funciona desde 1994 em São Paulo, o também bar e bicicletaria Las Magrelas, em Pinheiros, foi um dos primeiros adeptos da moeda virtual - desde maio de 2013.

Outro local que recentemente ganhou uma ATM de Bitcoins foi a Califórnia. O caixa eletrônico, operado pela Coinage, permite que o usuário compre Bitcoins usando dinheiro ou mesmo os venda por meio de uma carteira digital e saque o dinheiro correspondente.

O site colaborativo Coinmap permite que o usuário interessado confira quais os locais físicos espalhados pelo mundo que aceitam moedas virtuais.

Vivo lança sua própria Ad Exchange, a Axonix

Publicada em 16/04/2014 14:29

A Vivo acaba de lançar a Ad Exchange Axonix, para venda de publicidade direcionada em dispositivos móveis, baseada em dados demográficos e localização em tempo real de seus clientes.

A operação, com sede em Londres, recebeu aporte da empresa de investimento Blackstone. Usará a tecnologia programática Mobclix, adquirida da Velti, e começará com foco na América Latina, onde a publicidade móvel está na sua infância e as grandes empresas de Internet têm uma presença limitada. Mas também atuará nos mercados europeus e dos EUA.

“O programático é algo que nós estávamos olhando como uma estratégia de longo prazo para o negócio de publicidade”, disse à Mobile Marketing Magazine Simon Birkenhead, CEO da empresa.

“Há muito poucos dados disponíveis para os anunciantes utilizarem na segmentação de publicidade em móvel, As operadores têm um banco de dados muito rico de dados demográficos, dados de localização em tempo real e outros indicadores comportamentais de interesse das marcas”, afirma Birkenhead.

Dados da Vivo não serão integrados na plataforma de imediato, mas esse processo vai acontecer país a país começando com Alemanha e Brasil, onde a Vivo já mantém uma unidade de apoio à iniciativas de publicidade.

No último Mobile Day, realizado semana passada pelo IAB Brasil, Andreza Santana, Head of Mobile Advertising da Telefònica Brasil, contou um pouco como a Vivo vem encarando o mercado de publicidade móvel. De acordo com ela, em janeiro de 2013, já seguindo uma tendência global, a empresa resolveu abrir aqui uma unidade de negócio para tratar de advertising em dispositivos móveis. Hoje essa unidade tem 24 funcionários dedicados a ajudar os anunciantes e as agências de publicidade no desenvolvimento de ações e campanhas.

Só em 2013, seu primeiro ano de atuação, essa unidade entregou no Brasil 723 campanhas para 125 marcas. “O Brasil já é referência para outros países da América Latina e, até em alguns casos, para a Europa”, disse Andreza.

Hoje a Vivo tem 98 milhões de clientes no país, dos quais 55 milhões são opt-in. E mesmo com uma atuação maior no segmento de publicidade móvel em 2013, a operadora registrou um percentual inferior a 1% de opt-out.

“Nossa maior preocupação é a relevância do anúncio”, explica Andreza. “Nossa missão é fazer com que cada anúncio que o cliente da operadora receba seja um presente e não um incômodo. A sensação do cliente deve ser na linha do isso era o que eu queria, agora, nesse lugar”.

De acordo com a executiva, um bom exemplo do potencial da operadora para segmentação de anúncios com dados demográficos e de geolocalização foi a ação feita recentemente pela Vivo com o McDonald’s do shopping Vila Olímpia. Além de segmentar por perfil de clientes (classe social, idade, etc) definido pelo McDonald’s, a Vivo procurou, entre seus clientes, por pessoas que frequentemente acessavam as antenas localizadas no entorno do shopping. “Não foi uma geolocalização em tempo real, mas por histórico de uso”. Para esse grupo, foi enviada uma mensagem com uma oferta relevante: na compra do produto em promoção, aquele usuário ganhava outro igual, de graça. O resultado da ação, feita em um único dia, levou 400 pessoas para a loja da rede fast food.

“A geolocalização é bastante eficaz para o varejo”, afirma Areza. No ano passado a Vivo chegou a vender 90 mil pizzas para um único estabelecimento, fazendo disparos de segunda à quinta com promoções, só para assinantes daquela área (segmentação pelo CEP).

Agora, para a Copa, a Vivo já fará campanhas baseadas na localização em tempo real. “Serão ações diversas”, diz ela. Bancos, por exemplo, podem alertar clientes em viagens ao extetior, para não esquecer de desbloquear o cartão de crédito.

Segundo Areza, o big data também é uma grande tendência que a operadora tem usado internamente, para incluir um componente comportamental na segmentação e ser o mais preciso possível. É possível detectar, por exemplo, grupos de usuários profissionais, usuários fashion, usuários conservadores, guerreiros, tudo isso graças à análise de hábitos coletivos de uso.

O maior cuidado da Vivo é o mesmo que a Axonix promete ter: não perturbar os clientes da operadora e garantir sua privacidade. “A Axonix não manterá informações que possam identificar usuários individuais”, afirma Simon Birkenhead. “Mas há uma consciência crescente entre os consumidores de que para obter uma melhor experiência, tem de haver alguma troca de dados”.

Birkenhead vinha trabalhando na Telefónica Digital como diretor de vendas de publicidade globais nos últimos dois anos.

The Limits of Social Engineering

Tapping into big data, researchers and planners are building mathematical models of personal and civic behavior. But the models may hide rather than reveal the deepest sources of social ills.

- By Nicholas Carr on April 16, 2014

In 1969, Playboy published a long, freewheeling interview with Marshall McLuhan in which the media theorist and sixties icon sketched a portrait of the future that was at once seductive and repellent. Noting the ability of digital computers to analyze data and communicate messages, he predicted that the machines eventually would be deployed to fine-tune society’s workings. “The computer can be used to direct a network of global thermostats to pattern life in ways that will optimize human awareness,” he said. “Already, it’s technologically feasible to employ the computer to program societies in beneficial ways.” He acknowledged that such centralized control raised the specter of “brainwashing, or far worse,” but he stressed that “the programming of societies could actually be conducted quite constructively and humanistically.”

The interview appeared when computers were used mainly for arcane scientific and industrial number-crunching. To most readers at the time, McLuhan’s words must have sounded far-fetched, if not nutty. Now they seem prophetic. With smartphones ubiquitous, Facebook inescapable, and wearable computers like Google Glass emerging, society is gaining a digital sensing system. People’s location and behavior are being tracked as they go through their days, and the resulting information is being transmitted instantaneously to vast server farms. Once we write the algorithms needed to parse all that “big data,” many sociologists and statisticians believe, we’ll be rewarded with a much deeper understanding of what makes society tick.

One of big data’s keenest advocates is Alex “Sandy” Pentland, a data scientist who, as the director of MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, has long used computers to study the behavior of businesses and other organizations. In his brief but ambitious new book, Social Physics, Pentland argues that our greatly expanded ability to gather behavioral data will allow scientists to develop “a causal theory of social structure” and ultimately establish “a mathematical explanation for why society reacts as it does” in all manner of circumstances. As the book’s title makes clear, Pentland thinks that the social world, no less than the material world, operates according to rules. There are “statistical regularities within human movement and communication,” he writes, and once we fully understand those regularities, we’ll discover “the basic mechanisms of social interactions.”

Pentland’s idea of a “data-driven society” is problematic. It would encourage us to optimize the status quo rather than challenge it.

What’s prevented us from deciphering society’s mathematical underpinnings up to now, Pentland believes, is a lack of empirical rigor in the social sciences. Unlike physicists, who can measure the movements of objects with great precision, sociologists have had to make do with fuzzy observations. They’ve had to work with rough and incomplete data sets drawn from small samples of the population, and they’ve had to rely on people’s notoriously flawed recollections of what they did, when they did it, and whom they did it with. Computer networks promise to remedy those shortcomings. Tapping into the streams of data that flow through gadgets, search engines, social media, and credit card payment systems, scientists will be able to collect precise, real-time information on the behavior of millions, if not billions, of individuals. And because computers neither forget nor fib, the information will be reliable.

To illustrate what lies in store, Pentland describes a series of experiments that he and his associates have been conducting in the private sector. They go into a business and give each employee an electronic ID card, called a “sociometric badge,” that hangs from the neck and communicates with the badges worn by colleagues. Incorporating microphones, location sensors, and accelerometers, the badges monitor where people go and whom they talk with, taking note of their tone of voice and even their body language. The devices are able to measure not only the chains of communication and influence within an organization but also “personal energy levels” and traits such as “extraversion and empathy.” In one such study of a bank’s call center, the researchers discovered that productivity could be increased simply by tweaking the coffee-break schedule.

Pentland dubs this data-processing technique “reality mining,” and he suggests that similar kinds of information can be collected on a much broader scale by smartphones outfitted with specialized sensors and apps. Fed into statistical modeling programs, the data could reveal “how things such as ideas, decisions, mood, or the seasonal flu are spread in the community.”

The mathematical modeling of society is made possible, according to Pentland, by the innate tractability of human beings. We may think of ourselves as rational actors, in conscious control of our choices, but most of what we do is reflexive. Our behavior is determined by our subliminal reactions to the influence of other people, particularly those in the various peer groups we belong to. “The power of social physics,” he writes, “comes from the fact that almost all of our day-to-day actions are habitual, based mostly on what we have learned from observing the behavior of others.” Once you map and measure all of a person’s social influences, you can develop a statistical model that predicts that person’s behavior, just as you can model the path a billiard ball will take after it strikes other balls.

Deciphering people’s behavior is only the first step. What really excites Pentland is the prospect of using digital media and related tools to change people’s behavior, to motivate groups and individuals to act in more productive and responsible ways. If people react predictably to social influences, then governments and businesses can use computers to develop and deliver carefully tailored incentives, such as messages of praise or small cash payments, to “tune” the flows of influence in a group and thereby modify the habits of its members. Beyond improving the efficiency of transit and health-care systems, Pentland suggests, group-based incentive programs can make communities more harmonious and creative. “Our main insight,” he reports, “is that by targeting [an] individual’s peers, peer pressure can amplify the desired effect of a reward on the target individual.” Computers become, as McLuhan envisioned, civic thermostats. They not only register society’s state but bring it into line with some prescribed ideal. Both the tracking and the maintenance of the social order are automated.

Ultimately, Pentland argues, looking at people’s interactions through a mathematical lens will free us of time-worn notions about class and class struggle. Political and economic classes, he contends, are “oversimplified stereotypes of a fluid and overlapping matrix of peer groups.” Peer groups, unlike classes, are defined by “shared norms” rather than just “standard features such as income” or “their relationship to the means of production.” Armed with exhaustive information about individuals’ habits and associations, civic planners will be able to trace the full flow of influences that shape personal behavior. Abandoning general categories like “rich” and “poor” or “haves” and “have-nots,” we’ll be able to understand people as individuals—even if those individuals are no more than the sums of all the peer pressures and other social influences that affect them.

Replacing politics with programming might sound appealing, particularly given Washington’s paralysis. But there are good reasons to be nervous about this sort of social engineering. Most obvious are the privacy concerns raised by collecting ever more intimate personal information. Pentland anticipates such criticisms by arguing for a “New Deal on Data” that gives people direct control over the information collected about them. It’s hard, though, to imagine Internet companies agreeing to give up ownership of the behavioral information that is crucial to their competitive advantage.

Even if we assume that the privacy issues can be resolved, the idea of what Pentland calls a “data-driven society” remains problematic. Social physics is a variation on the theory of behavioralism that found favor in McLuhan’s day, and it suffers from the same limitations that doomed its predecessor. Defining social relations as a pattern of stimulus and response makes the math easier, but it ignores the deep, structural sources of social ills. Pentland may be right that our behavior is determined largely by social norms and the influences of our peers, but what he fails to see is that those norms and influences are themselves shaped by history, politics, and economics, not to mention power and prejudice. People don’t have complete freedom in choosing their peer groups. Their choices are constrained by where they live, where they come from, how much money they have, and what they look like. A statistical model of society that ignores issues of class, that takes patterns of influence as givens rather than as historical contingencies, will tend to perpetuate existing social structures and dynamics. It will encourage us to optimize the status quo rather than challenge it.

Politics is messy because society is messy, not the other way around. Pentland does a commendable job in describing how better data can enhance social planning. But like other would-be social engineers, he overreaches. Letting his enthusiasm get the better of him, he begins to take the metaphor of “social physics” literally, even as he acknowledges that mathematical models will always be reductive. “Because it does not try to capture internal cognitive processes,” he writes at one point, “social physics is inherently probabilistic, with an irreducible kernel of uncertainty caused by avoiding the generative nature of conscious human thought.” What big data can’t account for is what’s most unpredictable, and most interesting, about us.

Nicholas Carr writes on technology and culture. His new book, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us, will be published in September.

Failure Is the Best Thing That Could Happen to Google Glass

Photo: Ariel Zambelich/WIRED

Today, for one day only, Google Glass goes on sale to everyone in the U.S. Everyone, that is, with an extra $1,500 to spare and a desire to become a guinea pig in a hotly contested social experiment. It’s not a stretch to say that this little test, the first that hasn’t been geared to the already converted, could steer what Google ultimately decides to do with the entire project.

Until today, Google’s headwear has only been available in limited release through its Glass Explorer program. Making Glass widely available has ginned up predictable publicity that may give the impression of pent-up demand for Glass. But that demand is far from certain. People love to hate on Glass at least as much as users claim to love it.

If today’s sale fails, the future of Glass will be in doubt, and Google will have only itself to blame. The company hoped that through the sheer force of its awesomeness, it could circumvent the usual flow of novel technologies and bless the public with its grand design without being able to explain the need for it. Glass’ botched debut has created a brand stigma that may have already doomed the device.

But there’s another possibility: If Glass doesn’t sell today, maybe Google will take that as a sign to stop toying around and figure out how to make Glass really matter.

A Disastrous Roll-Out, to the Wrong People

Google has yet to make a convincing case that a wearable heads-up display is a necessity rather than a novelty. If today’s Glass sale flops, perhaps that could finally force an honest conversation about who and what the next generation of wearable tech is for, rather than simply trying to push a smartphone onto everyone’s face. It may mean that Glass’s future is more like that of a Taser than the iPad: That is, something geared to speciality, industrial use than mass-market ubiquity.

Since its release, the slow rollout of Glass has been a disaster, though not of the kind typically associated with new gadgets. By all accounts, Glass works as promised, and it brings a remarkable new kind of technology into the world. In the case of Glass, the failure has been social. Fairly or not, Glass has become an emblem of tech douchery before even leaving its testing phase. From a branding perspective, the rise of a derogatory nickname — “Glasshole” — for your new product’s users is a nightmare.

Aggrieved Glass lovers could play out the persecuted nerd narrative, or claim it’s a misunderstood work of genius ahead of its time. But such arguments miss a point that goes beyond Glass itself. While every big company believes it needs to move into wearables as the next big thing, no company has effectively defined the utility of devices like smartwatches and heads-up displays, at least for general consumer use. Because the need for a device like Glass hasn’t been well articulated, its use can come across all too often as gratuitously conspicuous consumption.

Yes, Glass fans might argue, but how are you supposed to know what it’s for until you take it out in the world and use it? The answer is that few digital technologies have really been put out into the world in as raw a form as Glass has. From smartphones to personal computers to the internet itself, the development of new computing technologies has almost always taken place in the realms of government, military, and business.

Photo: Ariel Zambelich/WIRED

Users in those worlds find that new technologies improve their ability to do a specific task. Eventually someone tries to extrapolate that usefulness to make something easier in the life of the everyday consumer, a quasi-organic process in which the utility of a technology evolves from the specific to the general.

With Glass, Google has tried to forcibly reverse that chain of adoption. Glass is a general-purpose device looking for a specific uses, and so far those uses haven’t been found to any meaningful degree. In a report earlier this year, Forrester Research analyst J.P. Gownder diagnosed this problem to argue that it’s the world of work that will drive real innovation in wearables as industries discover a vast range of tasks that body-attached technologies make better. From surgery to toxic-spill cleanup to installing cable, he says, any business that discovers a job that wearables make easier will rush to adopt that new technology.

Too Late?

Perhaps that’s why just last week Google announced its Glass at Work program, through which the company is basically trying to connect with businesses that are genuinely figuring out ways to make Glass useful. In that light, maybe today’s Glass sale is more like the end of something than the beginning. The sale lets Google gauge Americans’ demand for Glass; if that demand isn’t there, Google could take that as a signal to move its focus to the business uses where Glass might really make sense.

That could be the first big step Google takes not just toward figuring out what Glass is actually good for, but toward removing the “Glasshole” stigma. In San Francisco today, as tensions over tech-fueled gentrification escalate, Glass has become a signifier of “preening techie,” a stereotype that some wearers claim have made them victims of violence. But that stereotype will start to crumble the more Google can focus attention on the device than the user as a tool.

In many ways, a heads-up display like Glass makes the most sense for traditionally blue-collar work that could be enhanced by cameras, sensors, and metadata but still requires you to keep your eyes and hands on what you’re doing — think the construction site, the auto-body shop, or the factory floor. The more wearing a computer on your face becomes like wearing a tool belt around your waist, the less self-important it seems.

One way or another, wearable tech is here to stay. The better a job Google can do at demonstrating ways Glass can actually be useful in the world, the better a chance we’ll all have at reaching that future without calling each other names.

A partir de maio, Windows 8.1 sem Update estará vulnerável a ataques

Computadores com Windows 8.1 desatualizado poderão ficar vulneráveis. A Microsoft informou em nota no último sábado (12) que, a partir de maio, irá impedirá máquinas sem o o Windows 8.1 Update KB2919355 de receber atualizações de segurança, consideradas as mais importantes. Os pacotes devem ser baixados pelos usuários para evitar ataques de hackers e outras falhas no sistema.

Como instalar a atualização Windows 8.1 Update KB2919355 no computador

Update 1 do Windows 8.1 é obrigatório para receber atualizações de segurança do sistema (Foto: Divulgação/Microsoft)

A obrigatoriedade do Update 1 já era conhecida, mas a Microsoft reforça a importância da atualização para que os internautas tenham acesso aos pacotes de segurança e não só aos recursos de interface. Se os donos de PCs não fizerem o update de seus sistemas, deixarão de receber importantes reformulações no software e isso pode deixar a máquina vulnerável a ataques virtuais.

Segundo a Microsoft, os usuários que ainda não baixaram a atualização – porque optaram pela configuração manual do Windows Update – têm 30 dias para fazê-lo. Em maio, se o Update 1 do Windows 8.1 não tiver sido instalado, os novos updates de segurança serão considerados "não-aplicáveis" ao sistema.

Qual é o melhor Windows de todos os tempos? Comente no Fórum do TechTudo.

A limitação ocorre somente nos sistemas Windows 8.1 e Windows Server 2012 R2 (para empresas). Por isso, usuários de Windows 8 puro poderão ficar despreocupados, pois as atualizações continuarão a chegar para seus computadores normalmente.

A Microsoft não entrou em detalhes sobre o motivo da restrição, se limitando a dizer que, com a medida, pretende entregar uma experiência de suporte melhorada e unificada entre Windows 8.1, Windows 8.1 RT e Windows Server 2012 R2.

Via Microsoft