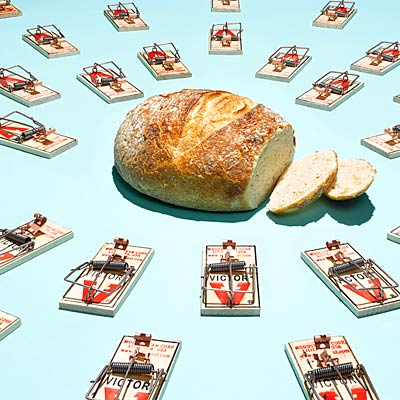

More and more women are slashing carbohydrates, hoping to slim down, feel energized and beat disease. But new research suggests a carb-starved, protein-centric diet might be hazardous to our health. Here's what you need to know before you pass up the potatoes.

Travis Rathbone

Does a plate of pasta strike terror in your heart? A burger in a bun make you break out in a cold sweat? You're not alone. These days, we're skipping the bread basket in record numbers (the volume of bread, buns and rolls sold in U.S. stores fell by 9.1 percent between 2006 and 2011) and shunning starchy vegetables. It seems like a new low-carb eating plan bursts on the scene every few months. And nearly one in three adults report that they're cutting down on or completely avoiding gluten, according to market-research firm NPD Group. "Carb-phobia has really taken over people's minds," says Kim Larson, RDN, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

But here's the thing: Eliminating carbs is risky business. "It's preposterous," says David Katz, MD, director of the Yale University Prevention Research Center and author of Disease-Proof. "All plants are carbohydrate sources, so eating no carbs means eating no plant foods, period." Carbs are important for your brain and body; the right ones even reduce your risk of disease.

Yet the misconception that the fewer carbs you eat, the better persists among health- and diet-minded Americans. "Everyone is jumping on this bandwagon," Larson says. "But the science just does not bear it out." In fact, studies now suggest that going low-carb for a long period of time may be harmful to our health.

Related: The Truth About 10 Bogus Health Trends

You can't live without carbs

While many of us think of carbs as bread and pasta, they're in any food that comes from a plant, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, grains, seeds and legumes. "It's a huge, diverse class of foods," Dr. Katz explains.

To make carbohydrates, plants trap the sun's energy inside molecules of glucose—a simple sugar—then connect the glucose molecules together (sometimes along with the other two basic sugar building blocks, fructose and galactose) to create longer carb molecules such as sucrose and starch. When you eat that plant, your digestive system breaks the longer carbohydrate back down into glucose, which travels through your bloodstream into your cells. The cells process the glucose, releasing the captured energy and using it for fuel.

Travis Rathbone

Far from being poison, then, glucose sparks life. "If you're in a hospital and they need to get some energy into you, they'll use a glucose drip," says Joanne Slavin, PhD, professor of food science and nutrition at the University of Minnesota and chair of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on Carbohydrates. Dr. Katz adds, "If you don't have enough glucose in your blood, you're dead. It's that simple."

While you don't have to eat carbs to get glucose into your blood (your body can manufacture it if needed), "carbohydrates are the most efficient fuel source that we have," says Heidi Schauster, RD, a nutrition therapist in Boston. Low-carb advocates (most famously Robert Atkins, MD) point out that your body can also use other fuel sources, such as protein or fatty acids, to power itself. But many experts say that this method of converting fats into so-called ketone bodies, known as ketogenesis, is much less efficient than using glucose for energy. And when too many ketone bodies are produced, the body is in a state of ketosis. "Ketosis can be tolerated for a short time, but in severe cases it could have very serious effects in the long term for the brain, as well as the kidneys, liver and skeletal system," Dr. Katz says.

Related: 11 Women Who Lost Weight Eating Healthy Carbs

Besides providing much-needed glucose, plants are our only source of dietary fiber. Like other carbohydrates, fiber is composed of many bonded sugar units, but human enzymes can't chop it up, so it passes relatively unscathed through much of the digestive tract. And it benefits you in many ways. "People who eat more fiber have less cardiovascular disease," Slavin says. "They also weigh less and gain less weight over time."

You probably know that fiber helps move food through your body, keeping you regular. In addition, some forms of fiber (including resistant starch, found in bananas, lentils and many other foods) are prebiotics, a type of carbohydrate that feeds the growth of "good" bacteria in your gut.

Not to mention, skipping carbs could mean falling short on essential nutrients. "Cutting out whole grains eliminates a good source of great nutrition, such as zinc, magnesium and B vitamins," Larson says. Steer clear of fruits and vegetables and you miss out on many vitamins and powerful antioxidants. These nutrients play a critical role in keeping us healthy long-term. "When we look at population-level studies of people who live well across the span of a lifetime," Dr. Katz notes, "they almost universally eat diets high in good carbohydrates."