| For the first time, scientists can take skin cells from people of various ages and transform them into brain cells reflecting the ages of their donors. By Faye Flam on October 9, 2015 Why It MattersAging is the number-one risk factor for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Studying how living human brain cells age could speed the development of treatments for disease and cognitive decline.

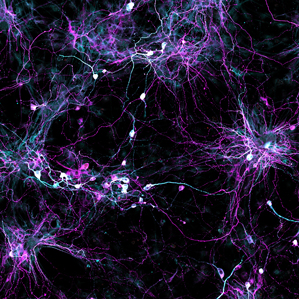

Scientists created these aging human brain cells not from old brains but from the skin cells of older people. Our brain cells change with age: various genes become more or less active, the membrane that holds the nucleus together starts to degenerate, and molecules that in young cells are neatly compartmentalized become scattered and disorganized. Now scientists have found a way to transform ordinary skin cells into living cultures of aging human neurons—test beds for ways we might reverse these effects of time. In the past, scientists have created neurons in a dish using stem-cell technology, but those efforts produced the equivalent of embryonic neurons. Jerome Mertens of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and his colleagues took skin cells from donors of different ages and transformed them into neurons that retained the effects of aging. This technique opens up new avenues for studying aging, age-associated diseases, and the possibility that drugs might stave off what was once inevitable. “These results are obviously going to have an impact,” says John Gearhart, director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not part of the study. The results will not only advance research into aging, he says, but could aid in the continued quest to create new cells to repair or replace damaged organs. Gearhart says that the new findings address a major problem in his field. There are several ways to force cells to switch from one type to another, but scientists haven’t been sure how the neurons made from a skin cell differ from the neurons that develop normally in people’s brains. The earliest method for reprogramming cells set the aging clock back to zero, he says, because the skin cells first had to be turned into a type of stem cell similar to those in early embryos. Mertens and his colleagues tried a newer technique, first developed at Stanford University, in which a series of biochemical tweaks switched skin cells directly into brain cells. What nobody knew, says Mertens, was how the cells created by this more direct route differed from the ones that had been first returned to an embryonic state. Were they making baby neurons or ones that reflected the ages of the donors? To find out, he and his colleagues collected skin cells from 19 people of different ages from infancy to 89, turned them directly into brain cells, and compared them with cells obtained from autopsies of people at different ages. They found that the transformed neurons carried certain telltale signs of aging in proportion to the age of the donors. Indeed, he says, they found that skin cells from older people could be turned into the equivalent of neurons from older people. They published their results in the latest issue of the journal Cell Stem Cell. The older neurons show different patterns of gene activation, says Martens. Age also disrupts what’s called compartmentalization—the ordered way in which some proteins stay confined to the nucleus of cells and others to the surrounding cytoplasm. Martens says the membrane separating the nucleus from the rest of the cell starts to fail, so as our cells age, more proteins end up in the wrong place. He’s eager to understand how this process affects the way our brains age and our susceptibility to diseases such as ALS and Alzheimer’s. The cell-transforming technique might also be expanded to produce three-dimensional structures called organoids, he says, which can be used as models of human organs.

http://www.technologyreview.com/news/542336/a-new-way-to-fight-aging-in-the-brain/ |

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.